The Raffles Conversation in BT on Hong Kong property executive Justin Chiu is well written and colourful, showing the man's innovative marketing side.

But Justin is definitely not in the same league as his big boss Li Ka-shing, whom I think has never been featured in the Raffles Conversation column. I hope to read Raffles Conversation on Li Ka-shing one day and other top personalities in Singapore and elsewhere.

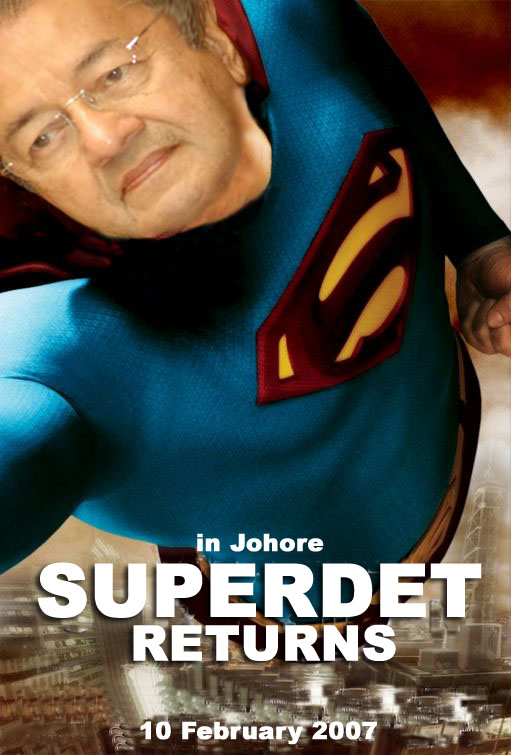

Property's rock star

Cheung Kong Holdings' Justin Chiu talks to ARTHUR SIM about revealing his wild side in the marketing of the Hong Kong conglomerate's property developments

MILD-MANNERED businessman by day, and the property-trade equivalent of a rock star by night, Justin Chiu has single-handedly made property launches glamorous affairs in Hong Kong, and some say in Singapore too, attracting the paparazzi frenzy usually reserved for movie stars.

For his elaborate efforts that go towards creating memorable events with each launch, Mr Chiu - an executive director of Li Ka-shing's Hong Kong conglomerate Cheung Kong Holdings and head of its property arm - is affectionately known in Hong Kong as 'The man with a 100 faces'.

For his elaborate efforts that go towards creating memorable events with each launch, Mr Chiu - an executive director of Li Ka-shing's Hong Kong conglomerate Cheung Kong Holdings and head of its property arm - is affectionately known in Hong Kong as 'The man with a 100 faces'.

In a recent incarnation, he dressed as an Arab sheikh to launch one Hong Kong development, simply because, 'everyone was saying that Middle East investors were coming'. (Units went for $5,300 per square foot, by the way.)

In Singapore, he has at various times led a bevy of beauties while dressed as James Bond and a convoy of Harleys in Easy Rider costume, all in the name of creative marketing.

Amazingly, Mr Chiu, 57, has only been in marketing and property development for 10 years with Cheung Kong. Before this, there was a four-year stint at Sino Land, and 15 years at Hang Lung Development Co. At these jobs, he was responsible for retail and commercial leasing as well as property management.

So when did he discover his wild side?

Mr Chiu joined Cheung Kong in 1997 and started doing sales and marketing in 2000. It was not the best of times for the property market and he knew he had to create buzz for an upcoming launch or there would be the real possibility that no one would come.

'I thought what we needed at the time was a spokesperson, or a movie star ... a sort of icon,' he recalls.

Celebrity endorsements are not a new concept, especially in Hong Kong. One only has to think of the many products that Jackie Chan has put his name to.

Mr Chiu, on the other hand, decided to create his own spokesman, and initially he had intended the position for his manager of the sales team. 'We were launching a seafront development at the time so I told my manager to come dressed as a naval commander.' Understandably, his manager refused.

Leading by example

So like any good boss, he decided to lead by example, and get into character himself. 'Anything is better than seeing another old man in tie,' he says.

The response, from the press at least, was unprecedented. And Mr Chiu's launch event occupied the covers of the property pages in the local media. A star was born.

'What we did was a great way of soft selling. People don't read ads but they do read the news. We also saved money on advertising, and we didn't need to pay for movie stars.'

Mr Chiu's instincts about marketing a product were right, a feat made more impressive by the fact that his educational background is founded on staid degrees in sociology and economics. But as he understands: 'What you study at university does not always relate to what you do for living.'

So far this year, Cheung Kong has earned up to HK$14.6 billion (S$2.8 billion) from the sale of 4,200 residential units. The turnover was more than double that for the same period last year and has already achieved the company's full-year sales target.

Selling property these days is a lot easier.

And Mr Chiu also does not really need to get dressed up any more, but he still does. 'The Hong Kong people have come to expect my 'special image' and reporters even want to know what I will be wearing next,' he says.

Now, Mr Chiu gets recognised in the streets. And overseas too.

He recalls how once, at the Changi International Airport, his Singapore staff was led to him by a small commotion from tourists shouting: 'Hey it's the Cheung Kong guy!'

Another time in a Chinese restaurant in New York, the waiter recognised him from the Chinese tabloids and Mr Chiu was seated immediately.

The going has not always been easy though, even for Easy Rider.

Cheung Kong's residential forays into the Singapore market began back in 1996 with acquisition by Li Ka-shing of a site in Thomson Road for $130 million. A year later, Cheung Kong bought an East Coast site for the then astronomical sum of about $680 million, 30 per cent higher than the next highest bid. The two purchases came just before the Asian financial crisis.

The developments came under considerable media scrutiny, not least because everyone wanted to know how Li Ka-shing, Asia's richest and shrewdest businessman, would get out of this one.

The task of moving units in a stagnant market fell on Justin Chiu and Cheung Kong's Singapore property arm, Property Enterprises Development. Mr Chiu got creative.

For starters, he devised an incentive scheme for the 390-unit Thomson project - Thomson 800 - something that had not been done before.

Under its Guaranteed Appreciation Plan, Cheung Kong was prepared to offer buyers a 10 per cent capital appreciation in about five years for units at Thomson 800 as well as protecting buyers against price falls of up to 10 per cent. If the valuation increased by less than 10 per cent above the purchase price, the developer would pay buyers the difference.

In essence, it was a kind of discount but unlike other developers who were offering outright money-off, this sounded more like a value-add. Clever.

The Asian financial crisis and its repercussions sent all property markets in the region into a tailspin. Only about half the units of Thomson 800 were sold, with City Developments finally buying the remaining units in 1999.

For the East Coast development - Costa del Sol - the situation was more dire because there were 906 units to move. Even the help of the bikers on Harley Davidsons could not stir the market, and only a third of the development was sold.

Amazingly, Cheung Kong went on to buy another site, this time in Cairnhill for $370 million, and again the property market dived with the aftermath of the terrorist attacks in the US on 11 September 2001.

The 248-unit Cairnhill Crest was launched in 2004 and Mr Chiu remembers how selling 40 units - after putting on an extravagant launch party with him dressed as James Bond - was quite an achievement at the time.

The 248-unit Cairnhill Crest was launched in 2004 and Mr Chiu remembers how selling 40 units - after putting on an extravagant launch party with him dressed as James Bond - was quite an achievement at the time.

But even then, Mr Chiu did something that was not often done here, and that was to go direct to his buyers by flying them in from Hong Kong and China.

Following his own advice

Today, properties do frequently sell out within weeks. But then, who can predict property cycles? And how important are they? Mr Chiu says: 'Whether the market is good or bad, developers must buy land.'

Fortunately, he heeded his own advice.

In 2001, Cheung Kong, together with joint venture partners Keppel Land and Hong Kong Land clinched a site in Singapore's New Downtown at Marina Bay for $462 million. Many sniggered behind their backs. 'At the time, everybody was saying that it was too risky,' remembers Mr Chiu.

But we all know what happened. The economy turned and the office building, One Raffles Quay (ORQ), went on to become one of the most talked about developments of the time, with all the big financial institutions clamouring to get in.

In July this year, Cheung Kong and Keppel Land each sold one-third stakes in ORQ to their sponsored real estate investment trusts (Reit), Suntec Reit and K-Reit, for $941.5 million each. Incidentally, Mr Chiu is also chairman of ARA Asset Management, which manages Suntec Reit.

In 2005, the same consortium won a tender for a commercial mega-site at Marina Bay to become major stakeholders in Singapore's new growth story.

Both ORQ and the newly dubbed Marina Bay Financial Centre have gone on to register 'over 100 per cent profit margin' for Cheung Kong. Indeed, as Mr Chiu reveals, 'all our projects in Singapore made money', although profit margins for the residential developments were considerably slimmer. For Cairnhill Crest, this was about 10-12 per cent.

On a philosophical note, Mr Chiu says: 'You cannot be winning all the time.'

But because Cheung Kong has very, very deep pockets, it can afford to hold off selling units, such as those at Costa del Sol and Cairnhill Crest, until the property cycle swings up again. The last block of Costa del Sol was sold in August for about $200 million, or $820 psf.

But this is only slightly higher than the launch price in 2000 and you do not need to be an expert to know that property prices are still rising.

Perhaps this is the real lesson here. All developers know that having the resources to hold on to property until prices pick up is the key to survival. Only a certain kind of developer believes that making a killing isn't everything - even when dressed up as 007.

Standing out from the crowd STEREOTYPES are fun. Especially if you are not the object of derision.

Wisely then, Hong Konger Justin Chiu refused to be drawn into the age-old discussion on why Singapore is just so different from Hong Kong. He would not say, for instance, if he agreed with the popular stereotype that Singapore is clinical and boring.

Or, for that matter, if Singaporeans lack verve and an entrepreneurial spirit.

He was, however, game to talk about 'Hongkies'. 'The competition in Hong Kong is very stiff. So if you want to be noticed, you really have to stand out,' says Mr Chiu, by way of explaining why Hong Kong people are perceived as show-offs, and why it has more Rolls Royces per capita than any other country in the world.

It probably also explains why according to this writer's own Louis Vuitton Index, Hong Kong ranks above Paris, New York, Beijing and Singapore, with a total of six stores.

Mr Chiu, an executive director of Hong Kong conglomerate Cheung Kong Holdings, knows a thing or two about standing out from the crowd. The eleventh child in a family of 14, he decided that getting a university degree was going to be his thing. 'During my time, getting a university degree was a big deal,' he says.

His beginnings, although not exactly humble, were not entirely privileged either. His father, he recalls, had only two wives. 'Most people had four,' he says, quite seriously.

His first degree was in sociology. Then realising that he needed something more practical, he took a second degree in economics at Trent University in Canada.

He cut his teeth in the real estate industry at Hang Lung Development Co in 1979 - still one of Hong Kong's larger property developers. But by 1994, finding that the pace of business had slowed too much for him, he decided to move on. 'I am actually quite aggressive,' he reveals.

So he joined Sino Land instead, the Hong Kong property arm of Singapore's richest man, Ng Teng Fong. Compared with the other Hong Kong developers, Sino Land was a relatively young company that had to prove itself, so it suited Mr Chiu for the three years that he was there.

'Sino Land had to be very aggressive in the market, especially in bidding for development sites at government land tenders because unlike older companies, it did not have the same contacts,' explains Mr Chiu.

Ng Teng Fong was not hands-on in the daily operations of Sino Land, leaving that to his son Robert. Still, the occasional meetings with the tycoon left him with a strong impression. 'If Singapore had more Ng Teng Fongs, it would be a lot more successful,' he says.

Mr Chiu, the father of two children in their twenties, is not impressed by the many young people he has met lately. 'Many just want stable jobs in government agencies or investment banks,' he notes. 'And in Singapore, if you can get a job in the civil service, the pay is actually quite attractive,' he added.

Mr Chiu does not think Hong Kong people are, like himself, 'aggressive'. He is of Shanghainese stock after all. Still, he does believe that Hong Kongers are more adventurous. 'They are prepared to take higher risks,' he says.

'Which is why,' he adds, 'reits (real estate investment trusts) are not very popular in Hong Kong. Hong Kong people think reits are boring. There is no capital appreciation. Singaporeans, however, like reits because it offers a stable income.'

This says a lot actually.

Mr Chiu is also the chairman of Cheung Kong's ARA Asset Management which manages Fortune Reit, which counts as its assets Hong Kong shopping malls. The reit, together with its Suntec Reit, were listed on the SGX mainboard and not the Hong Kong exchange.

So why does a man as dynamic as Justin Chiu - a man who rides a motorbike for his speed fix, skis, and until recently, para-glides - choose to work for not one but two of Asia's most dynastic companies?

Cheung Kong, Mr Chiu says, 'is very big'. The property arm alone has a 150 million sq ft landbank in China's first and second tier cities alone.

Mr Chiu also remembers being very impressed by Asia's richest man.

He was interviewed by Li Ka-shing personally for his job at Cheung Kong, and after the interview, Mr Li told him that the organisation values integrity above all. 'He also told me not to promise people anything that I don't think I can deliver,' recalls Mr Chiu.

On Mr Li's part, he also shows his subordinate mutual respect. 'I have been given a free hand to try new ideas,' Mr Chiu says, adding that Mr Li junior, Victor, is also very supportive.

And to his credit, the senior Li is always willing to listen. 'He would listen to you first and comment only when you are done. He never interrupted you. It really shows respect,' says Mr Chiu, laying to rest another stereotype.